Conducting

Beating Time

The basic purpose of a conductor is to make sure everyone starts and stops together and, during the intervening time, stays together. Exactly how you do this doesn't matter (as long as both you and the singers know what you are doing).

There are various conventions which we shall look at shortly, but many of these will have to be abandoned if you are both conductor and accompanist - in which case, a significant nod or twitch of any spare limb may have to suffice.

An overall feature of giving a beat is (apart from being regular) to use a flowing motion so that the hand is never stationary, and the actual moment of each beat is denoted by a little flick.

Here is an example of a rigid, wooden beat with no sense of flow and no perceptible flick to define the moment of the beat.

On the other hand, wild, flowing, windmilly beats are as equally hard to follow as rigid, wooden beats:

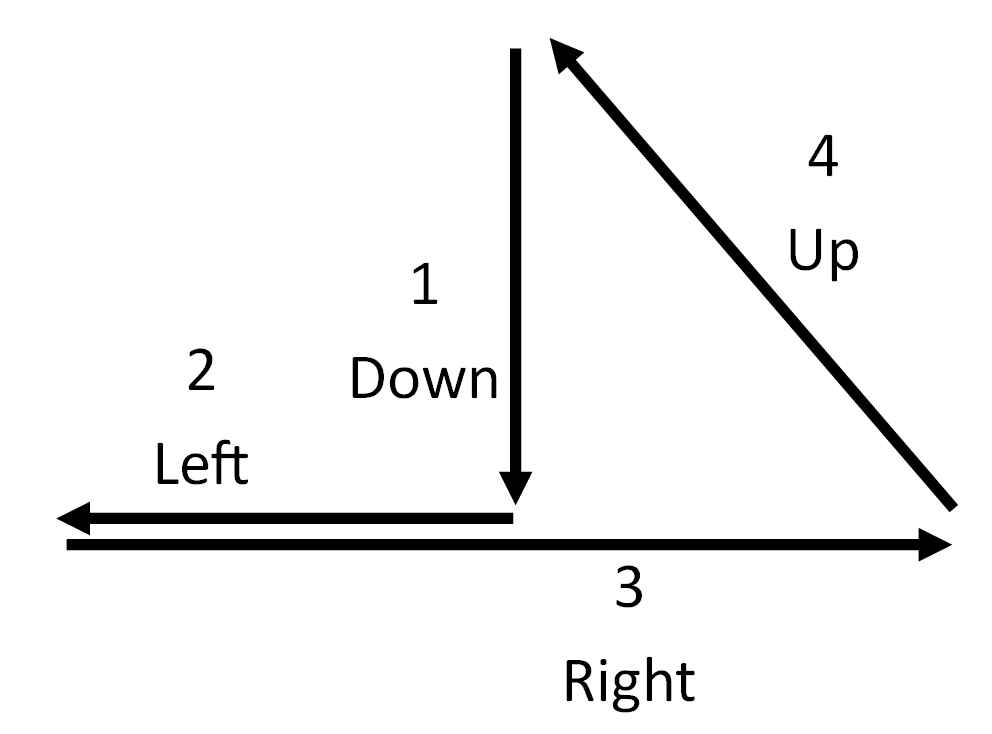

In the following examples, the graphic is shown from the point of view of you, the conductor; the video of how this appears to a choir.

The down beat defines the first beat of the bar.

Thinking through a few beats first helps to make sure that the preparatory beats

(which enable the choir to know how fast a piece is going and when to come in) are in the same tempo that your piece will actually be conducted. It's not unknown for conductors

to give preparatory beats that do nothing but confuse the choir.

Each example has two preparatory beats. This can be just one - or more that two - but it's important that both you and choir know how many there will be. One advantage

of having two preparatory beats is that a choir can learn to think deep breath with these beats.

It's important for the conductor to be completely still before giving the preparatory beats so that he or she is quite certain of the tempo to be used. Some conductors, quite naturally, seem to give some

subliminal coming together just before they give the beats.

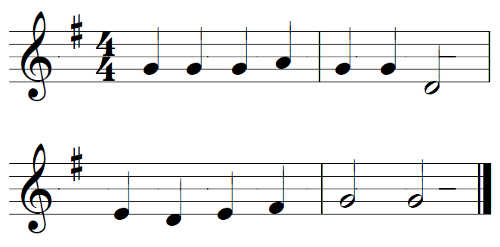

Duple Time

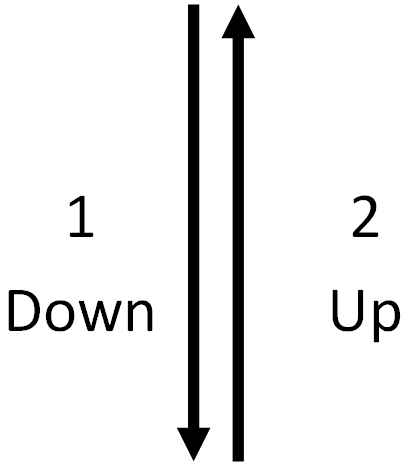

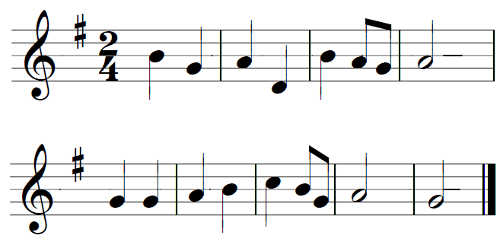

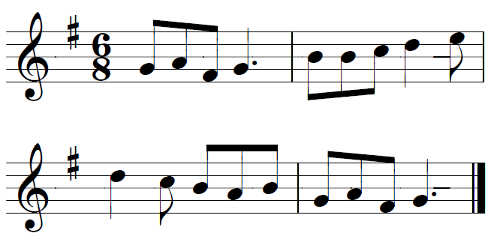

Here is a basic duple time (2/4, 2/2, 6/8 [6/8 is a compound duple time - see HERE.] etc). The preparatory beats are 1 and 2:

Diagrams like this are fine for showing the basic method of indicating beats, but may lead to a rigid beat as mentioned earlier. This video gives a better idea of how the beat should look. You will notice that the beat-defining flicks are all at about the same height.

Triple Time

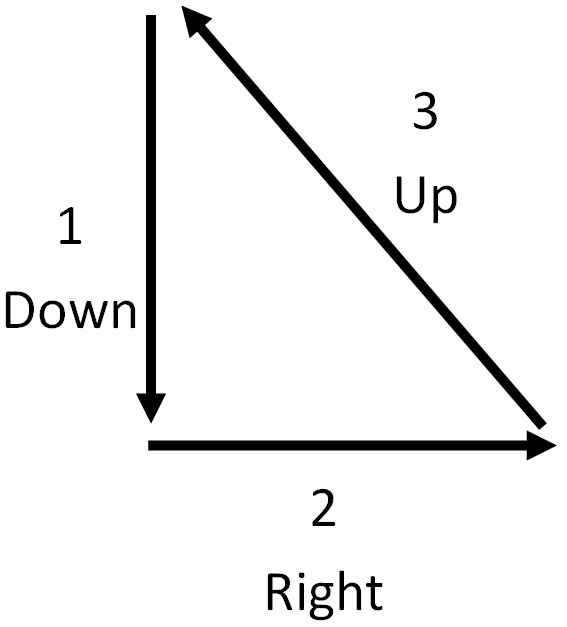

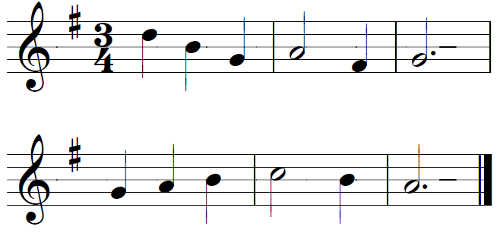

This is a basic triple time (3/8, 3/4, 3/2, 9/8 [9/8 is a compound triple time - see HERE.] etc) The preparatory beats are 2 and 3:

Which will look something like this:

Quadruple Time

A quadruple time (4/8, 4/4, 4/2, 12/8 [12/8 is a compound quadruple time - see HERE.] etc) looks like this - with beats 3 and 4 as preparatory beats:

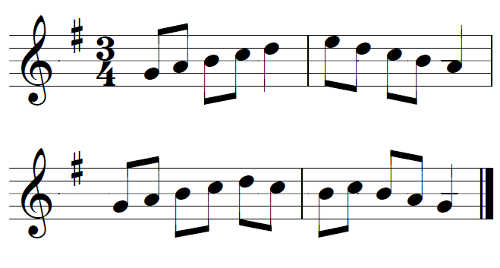

Triple Time with Divided Beats

Sometimes, in slower music, you may want to divide the beat to retain better control of the singers. Here is a triple time with little flicks on the half beats, counting |1 and 2 and 3 and|1 and 2 and 3 and|:

Quadruple Time with divided beats

Similarly, a divided quadruple time has little flicks on the half beats:

Duple Time with Divided Beats

If you wanted to divide the beat in a duple time, just beat in four (but make sure that the choir knows what you are doing).

6/8 with Quaver Beats

6/8, being a compound time signature, is really two beats in a bar, but if you need to conduct in quavers rather than dotted crotchets, two subsidiary flicks are needed for every beat. (from now on, graphics will probably be less than helpful):

You may want to go back and compare how this differs from 3-4 with divided beats (as both 3-4 an 6-8 have six quavers in a bar. The difference is:

- 3/4 is counted and conducted: |1 and 2 and 3 and |1 and 2 and 3 and|

- 6/8 is counted and conducted: |1 and a 2 and a |1 and a 2 and a|

Of course, if the time signature is 6/4, you could conduct in crotchet beats.

9/8 with Quaver Beats

It's best, if possible, to conduct 9/8 as three beats in the bar, but if it's necessary to divide the beats

(Or 9/4 with crotchet beats.)

12/8 with Quaver Beats

Similarly, 12/8 is best conducted as a quadruple time, but if it's necessary to divide the beat:

Return to:

TOP

MENU - The Choir Trainer's Toolkit

MENU - Organists Online

Up Beats

Some pieces don't begin on the first beat of the bar. They have an upbeat or anacrusis.

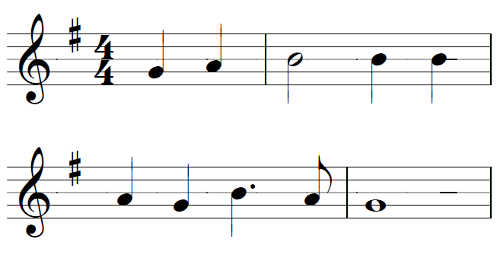

Triple Time with an Upbeat

Here is a triple time, with an upbeat, and beats 1 and 2 as preparatory beats:

Quadruple Time with an Upbeat

And here is a quadruple time with an upbeat, and beats 2 and 3 as preparatory beats.

Multiple Upbeats

Slightly rarer, but far from unknown, are pieces with several up beats. In this example of quadruple time, the music starts on beat 3, so the preparatory beats are 1 and 2:

Return to:

TOP

MENU - The Choir Trainer's Toolkit

MENU - Organists Online

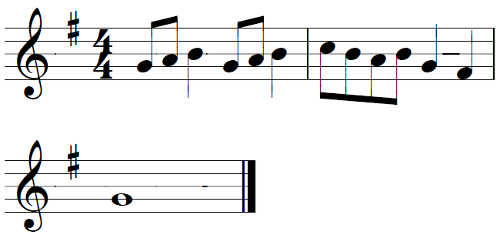

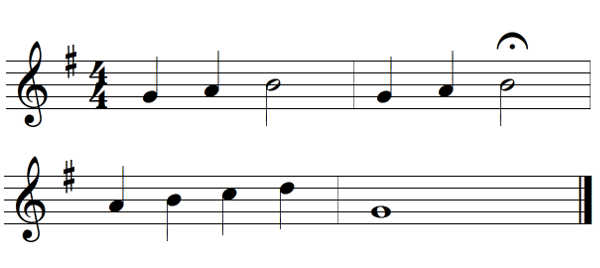

Pauses

Pauses are places where the regular beat of the music ceases and a prolongation or a gap of unmeasured time exists. These occasions are rich in opportunities for a choir to fall to pieces.

Although, artistically, pauses are supposed to respond to the emotion of the moment, it's quite helpful to have worked out exactly how long they are going to last (sort of adding extra beats to the bar). This

may be considered inartisitic, but the congregation is not likely to notice the artifice, and the choir will be more confident.

In this example, there is no gap after the pause; the choir just holds the note and then carries on.

The second bar could be counted as: | 1, 2, 3 and (with the baton/hand almost still on the and) 4 | 1 etc. Beat 4 is used to gather up the singers to carry on.

The second bar could be counted as: | 1, 2, 3 and (with the baton/hand almost still on the and) 4 | 1 etc. Beat 4 is used to gather up the singers to carry on.

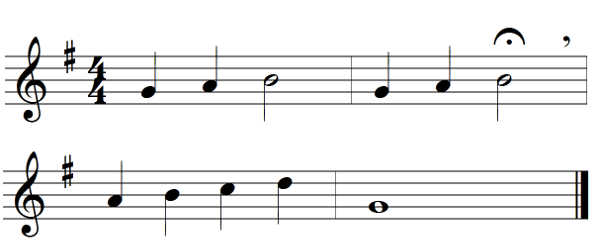

In this example, there is a definite break after the pause.

The second bar could be counted as: | 1, 2, 3 and and 4 | 1. In this case, beat 4 is more pronounced as the singers are encouraged to break and maybe breath.

Return to:

TOP

MENU - The Choir Trainer's Toolkit

MENU - Organists Online

Eye Contact

Theoretically, a choir should be able to follow a clear beat - whatever else the conductor is doing, but it doesn't really work like this.

At vital points (entries, endings, pauses, changes of tempo etc) the conductor should fix and compel the choir by eye contact. Many a performance has

come to grief because a nose-in-the-copy conductor failed to look at the choir and they (to a man and woman) lacked the confidence to start without

the added stimulus of an encouraging or demanding gaze.

Return to:

TOP

MENU - The Choir Trainer's Toolkit

MENU - Organists Online

The Other Hand

So far, everything has been about what the beat-giving hand does (which, professionally, would be the right hand, but this doesn't really matter). The other

hand is useful for interpretive direction (crescendo, diminuendo etc) and pointing to individual parts as they come in. Otherwise, let it be still. There's

not much to be gained in using it to mirror-image what the beat-hand is doing.

Still Time

Before beginning a piece, let there be a moment of stillness. This has two purposes:

- it gives you time to make sure you have the tempo you want in mind;

- the choir can be quite sure when you start to give the preparatory beats. Any other movements at this time could be confusing.

Return to:

TOP

MENU - The Choir Trainer's Toolkit

MENU - Organists Online